|

| Our young hero in 1946. |

Louis Franklin “Lou” Laramore was born in Los Angeles in 1923. The son of a bond salesman, he played football for Whittier College and ended up married and divorced at least a few times. By age 31 he was already developing a large housing tract at Magnolia Ave and Crescent in Anaheim. It’s unknown whether this was his first subdivision project, but it certainly would not be his last.

|

| Colonial, English, Hawaiian, Storybook, Western and Modern designs were available in the Eastgate development (Long Beach Press-Telegram) |

Free to go on about his business, Laramore began numerous new developments. By 1964, Laramore was president of World Wide Construction Company of Newport Beach, "builders of Laguna Real homes in Laguna Hills." Laguna Real was a "planned home community in the coastal Laguna Hills just south of El Toro." It was actually on the inland/El Toro side of the Freeway. By mid-1964, Laguna Real was 567 acres with plans for 2,000 homes. (And despite the name, there was no “royal lagoon” to be found there.)

|

| Laguna Real billboard, El Toro, Oct. 6, 1964. |

In 1962, Laramore also started the Moral Investment Co. in order to develop about 167 acres near El Toro into 700 low-priced single-family homes in what he called the Moral Investment Planned Community (Tentative Tract #4848). The land was north of El Toro Road, on the south side of Valencia Ave, east of Moulton Parkway and west of the San Diego Freeway – Immediately under the flight pattern used for instrument landings by the military pilots coming in to MCAS El Toro.

Neither the Marines nor the County of Orange wanted high density population immediately in harm’s way if a plane should come down. The Marines also feared that if development were allowed to occur on the property, future complaints about noise and safety would jeopardize the very existence of the base. Laramore had no such concerns about the public or the base.

|

| Moral Investment Planned Community map, 1968 (C-R OR 8615/958) |

In February 1963, while Laramore was still in the planning process, the County changed the zoning to permit only light manufacturing, rendering his plans useless. As if to illustrate the County’s point, a jet crashed on the Moral Investment Co. property that August. (The crew ejected safely.)

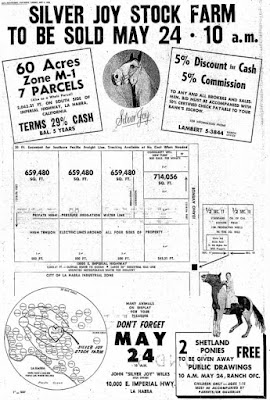

The Moral Investment Co. drained its own resources with a series of lawsuits. They tried to have the zoning reversed. They tried to have the zoning change made unconstitutional. They tried to have the County pay them for the "lost value" of the property. They fought and fought and eventually won a pyrrhic victory -- getting the area at least partially reopened to development. Even then, the County indicated it would appeal.

In the middle of all this, the groundbreaking for Laramore’s Laguna Real was held in March 1964. Ironically, the ceremony featured a helicopter from Marine Corps Air Station El Toro and three Orange County Supervisors.

|

| Laguna Real groundbreaking, 1964: (L to R) Supervisor David L. Baker, Laramore, unidentified horse, Supervisors Cye Featherly and Bill Hirstein (Long Beach Independent Press-Telegram) |

Meanwhile, Cortese was contemplating a second Leisure World development (the first was near Seal Beach) near El Toro, and included a strip with golf-courses and other low-density uses under an adjacent portion of the flightpath. He managed to make it work.

But Laramore was hardly done tangling with the law. He was still developing properties in Riverside County, where the Fair Political Practices Commission slapped him with a $138,000 fine (a national record at the time) for laundering money for the benefit of the Supervisorial candidate in 1991. Laramore was also charged with criminal offenses by the Riverside County District Attorney. He died a free and presumably wealthy man in Upland in 2000.

|

| Area map showing location of Moral Investment Planned Community, 1968 |

After voters repeatedly rejected their bid to kill the airport at the polls, the developers put it on the ballot yet again, this time promising that MCAS El Toro would become a Great Park. Of course, the Great Park was destined to mainly be “more Irvine,” with residential and commercial development. But the lie served its purpose, with developers and their consultant friends set to reap the rewards.

Moral indeed.