|

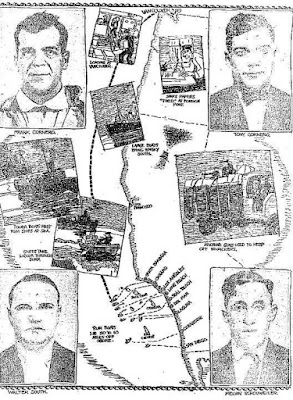

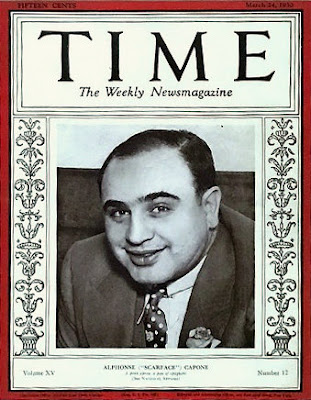

| Map with photo from Liberty Magazine, May 1931. |

How different would South Orange County and North San Diego

County be today if Al Capone had owned much of that land in the form of the

massive Rancho Santa Margarita? It could have happened.

The Rancho Santa Margarita, was granted by Governor Juan

Bautista Alvarado of Alta California in 1841 to Andrés

Pico and his brother, Pio Pico who would later serve as the last Governor of Alta

California under Mexican rule. It was one of the largest land grants in Southern

California. Three years later the Picos were also

granted the adjacent Rancho Las Flores, and the name of the combined properties

became Rancho Santa Margarita y Las Flores. This land today makes up Marine

Corps Base Camp Pendleton in San Diego County.

|

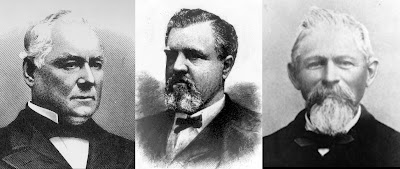

| Andrés & Pio Pico. Image of Andrés (left) circa 1875, courtesy California State Library. Image of Pio Pico courtesy Bowers Museum. |

In 1864 Pio Pico’s brother-in-law, Englishman-turned-Californio

Juan Forster, paid $14,000 and assumed all of Pico’s

gambling debt in exchange for ownership of Rancho Santa Margarita y Las

Flores. [i] Forster had lived in what remained of Mission San Juan

Capistrano for twenty years. He already owned the Rancho Mission Viejo

and the Rancho Trabuco which today include the cities of Rancho Santa Margarita

and Mission Viejo, the community of Coto de Caza, part of San Clemente, Caspers

Wilderness Park, O’Neill Regional Park, a large swath of the Santa Ana

Mountains, and all the remaining land of the modern Rancho Mission Viejo Company. [ii] Forster also held land patents on Potrero de la Ciénega, Potrero

el Cariso, and Potrero Los Pinos. He

added his new rancho to his existing ones, combining them into one enormous

Rancho Santa Margarita.

|

| Key ranchos that made up the "supersized" Rancho Santa Margarita." (Map by author) |

After Forster’s death in 1882, the

combined ranch was sold to James Flood – “The King of the Comstock Lode.” In 1906

the Floods gave half ownership to their ranch manager, Richard O’Neill. [iii]

After the deaths of James Flood and Jerome O’Neill (Richard’s

son and successor) only a couple months apart in 1926, it was unclear what

would happen to the ranch. Would the estate administrator subdivide it, sell it

off as one block of land, or find another way to dispose of it? The fate of the

property sat in limbo.

|

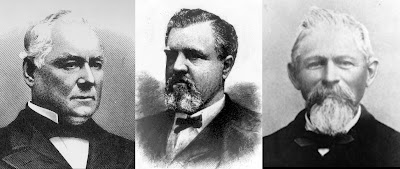

| (L to R) Juan Forster, James Flood, and Richard O'Neill, Sr. |

But one of the few men in America wealthy enough to buy that

much land would get his first look at it soon.

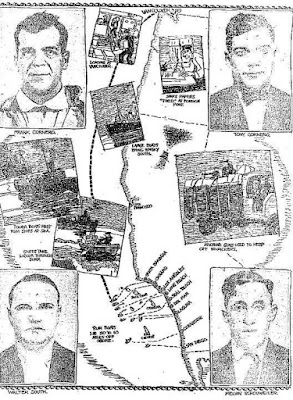

The infamous Alphonse “Al” Capone (a.k.a.

“Scarface”) was the head of the crime syndicate known as the Outfit. This Chicago-based

mob was involved in everything from gambling to protection rackets to brothels.

But its focus and income rested on the bootlegging of liquor. Trying to build and

maintain a near monopoly on alcohol during Prohibition meant years of “Beer Wars,”

bombings, and assassinations between rival gangs. Capone ruled Chicago the way

modern drug cartels rule Mexico.

|

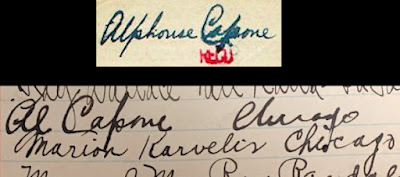

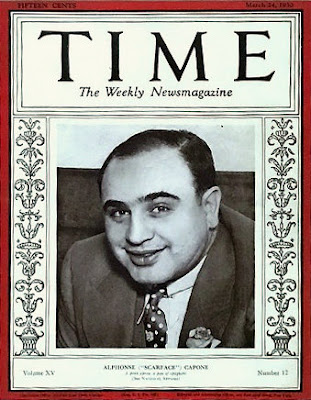

| Alphonse Gabriel "Al" Capone, 1929 |

In November 1927, Capone thwarted

a well-organized attempt on his life by a rival gangster. Soon after, Chicago

Mayor and would-be Republican presidential nominee Big Bill Thompson told

Capone to leave town so he could claim he finally had control of the city. [iv]

Meanwhile, the press continued their almost daily narrative of Capone’s evil doings

(both real and imagined) as America’s best-known criminal kingpin.

At the beginning of December, Capone

told the press he was leaving for St. Petersburg, Florida and didn’t know if he

was coming back. “Let the worthy citizens of Chicago get their liquor the best

way they can. I’m sick of the job. It’s a thankless one and full of grief.” He

described himself as a misunderstood public benefactor and mused about what the

city would be like once he left. “I guess the murder will stop,” he said.

“There won’t be any more booze. You won’t be able to find a crap game even, let

alone a roulette wheel or a faro game… The coppers won’t have to lay all the

gang murders on me now. Maybe they’ll find a new hero for the headlines. It

would be a shame, wouldn’t it, if while I was away they would forget about me

and find a new gangland chief?”

On December 6th Capone and

two of his bodyguards got on a train for Southern California, not Florida. It

was a trip, he later said, just to see the sights. “This is just a pleasure

trip, and I'm just a peaceful tourist." [v]

|

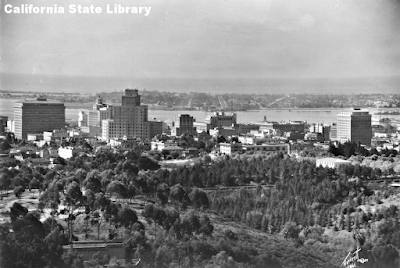

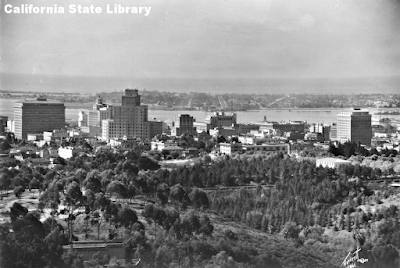

| San Diego's business district, late 1920s. |

Newspapers reported that Capone had

barely arrived in Los Angeles when he got on another train heading south, spending

December 9th visiting San Diego and supposedly the races and

bullfights in Tijuana. He had plenty of time to admire the Rancho Santa

Margarita from the windows. The stories also mentioned that he was accompanied

not only by his bodyguards, but also his “wife” on this excursion. [vi]

(Capone’s actual wife of nine years, Mae, had not come with him to California.)

Capone later confirmed that he’d been to San Diego that week. “I had a fine

time,” he said of his trip, “…especially in San Diego where lots of people invited

me to visit them.” [vii]

No evidence has thus far been

unearthed that Capone actually got as far south as Tijuana, suggesting that San

Diego was the focus of his trip. [viii]

The press never stated how Capone spent his time in San Diego, which may

suggest that he was not out “seeing the sights,” where he would have been easily

recognized.

|

| Marion Karvelis, from her naturalization papers, circa 1937. |

On the way back up to Los Angeles,

on December 10th, Capone again passed through the massive Rancho Santa Margarita and stopped

in San Juan Capistrano. He added his signature to Mission San Juan Capistrano’s

guest register that day: “Al Capone, Chicago.” This signature closely matches other

confirmed autographs of the gangster. The next signature, immediately under Capone’s

in the register, is that of Marion Karvelis of Chicago[ix],

– a 23-year-old, blonde vaudeville dancer who worked in several Chicago-area nightclubs

owned by or connected to Capone and his brother. [x]

It’s likely Karvelis was the woman the press had mistaken for Mrs. Capone the

day before. [xi]

|

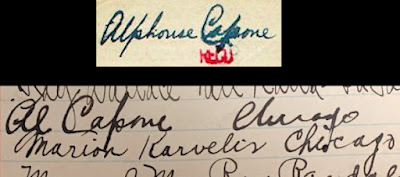

Above: Confirmed Capone signature from a 1923 check. (Courtesty MyAlCaponeMuseum.com)

Below: Signatures of Capone and Karvelis in the Mission Guest Register, Dec. 10, 1927 (Courtesy Mission San Juan Capistrano Museum) |

According to Los Angeles Times

columnist Harry Carr [xii],

Capone visited the Mission’s historic and newly restored Serra Chapel with a “companion”

and tried to buy one of the Stations of the Cross paintings from the padres.

"You'd better put a price on

it," Karvelis told a shocked priest. "When my friend decides he wants

a thing, he gets it."[xiii]

|

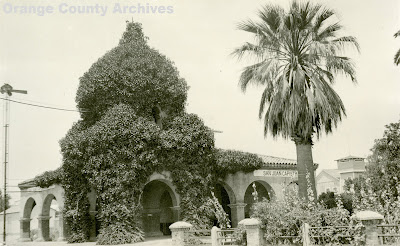

| Serra Chapel with paintings still on walls. (Photo by author) |

At that time, the only priests at

the Mission were the ailing Fr. St. John O’Sullivan – who’d restored the Mission,

made its swallows famous, and inspired the restoration of the rest of California’s

Spanish Missions – and his brother, Fr. Anthony O’Sullivan, who’d been sent to

assist him. [xiv]

The notion of Capone and Karvelis facing off against either of these

clergymen is strange indeed.

|

| Fr. St. John O'Sullivan (1874-1933) |

As for the stations of the cross, all

but one of the fourteen paintings in this series were brought to the Mission

from Mexico sometime between the 1780s and early 1800s.[xv] The twelfth painting went missing early

in the Mission’s history and had later been replaced with a larger version of the

same scene. [xvi]

It is unknown which scene of the Passion of Christ most appealed to the gangster.

In any case, Capone didn’t get the

painting. He did, however, have another good long opportunity to admire the

surrounding ranch land.

|

| Two of the Serra Chapel's Stations of the Cross. (Photo by author) |

Capone and his entourage returned

to Los Angeles, checked into the Biltmore Hotel, and quickly found themselves under

heightened scrutiny by the local press and law enforcement. On December 13th,

Capone and his two associates were escorted by police detectives to the Los

Angeles Santa Fe Railroad station and were placed on a train back to Chicago.

Notoriously thugish Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) Detective Edward D. "Roughhouse"

Brown [xvii]

was the unwelcome chaperone in charge of making sure Capone and his men left

California, pronto. [xviii]

|

| Roughhouse Brown, L.A. Evening Express, Jan. 31, 1930 |

"I just came here for a

little rest," Capone protested. "We are tourists and I thought you

people liked tourists."[xix]

As they put him aboard the train, he continued, “I have a lot of money to spend

that I made in Chicago. Whoever heard of anybody being run out of Los Angeles

that had money? I’m all burned up, but you can’t keep me away…"[xx]

|

| The San Juan Capistrano train depot - just steps from the Mission. (Courtesy OCA) |

After what the press dubbed his “brief

excursion among the orange juice stands of southern California, [xxi]"

Capone resolved that Los Angeles was the "wrong town" for him. But he

said he liked the countryside and that he intended to return to Southern

California. "...I like the country. I'm coming back pretty soon. …When I

get a little business done in Chicago, I'm going to send out a lot of money

here and have some real estate man buy me a large house. Then I'll be a taxpayer

and they can't send me away. Anyway, when the real estate men find out I've got

money they won't let me go, even if I want to."[xxii]

After a time, Capone began looking

for a real estate broker who could not only handle a transaction as large as

the purchase of the Rancho Santa Margarita, but who’d also be discreet about the

identity of his client. At that point, Capone’s only other significant foray

into buying property outside the Chicago area was in St. Petersburg, Florida during

the mid-1920s. He and fellow mobsters Jake Guzik and Johnny Torrio (Capone’s

mentor) were the silent partners in the deal while their general partner,

Florida real estate broker Robert Vanella, arranged to purchase a good deal of

land with little fuss. [xxiii]

[xxiv]

California wouldn’t be so easy.

“Heads of a local real estate firm

are said to have reported three men representing themselves as agents of Capone

recently offered $200,000 for an option on the [Santa Margarita] ranch… and attempted

to rush the deal...” reported the Associated Press.[xxv]

The trio would not disclose the intended use of the land, but said that “Capone

has a desire to live in California and wants to buy the land before authorities

prevent him, as they did in Santa Barbara.”[xxvi]

|

| Ed Fletcher, circa 1935 (MSS 81, Special Collections, UC San Diego) |

Within a year or so of his visit,

it seems Capone quietly retained Col. Edward "Ed" Fletcher to facilitate

his acquisition of the Rancho Santa Margarita.

Fletcher was a prominent San Diego

real estate broker, land developer, civic leader, and a central figure in the

early development of the county’s water resources and highways. A mover-and-shaker

in the county’s Republican Party, he would later serve as a California State

Senator. Fletcher’s real estate clients were generally rich men from outside the

San Diego area who provided financing while leaving the logistics to him. [xxvii]

In early July 1929 Fletcher launched

and then led a long and successful campaign to have the tax assessment on the

San Diego County portion of the Rancho Santa Margarita raised dramatically. [xxviii]

This would make the sale of the ranch significantly more appealing to its owners.

Fletcher’s client seemed to have many alternate forms of income – to say

nothing of potential ways to dodge taxes altogether. But true ranchers held

most of their wealth in their land and could little afford major increases in

their property tax.

Just days after the opening salvo

in his tax fight, Fletcher told the San Diego Board of Supervisors (and by extension,

the press) that the ranch should be "offered for sale for $10,000,000 on reasonable

terms... I can sell the property at that figure in a few months, charging only

the usual commission."[xxix]

The Board agreed that the assessment

should be raised by $700,000. [xxx]

|

| A younger portrait of Charles S. Hardy. (Smyth, 1913) |

From the start, Charles S. Hardy, the

manager of the Rancho Santa Margarita, was the primary opponent to increases in

the ranch’s assessed value.

For over forty years, Hardy had been

among the leading political, commercial and civic figures in San Diego County. He'd

come to San Diego in 1881, managing cattle interests for a butchering company

before opening his own market in 1882, followed by his own meat packing business.

For many years he had a near monopoly on meat within the county, earning him a

fortune. [xxxi]

“Charles S. Hardy understands the

cattle business in every one of its innumerable details from the running,

feeding and fattening of the animals on the ranch to the slaughtering, curing

and selling in the city markets” wrote William Smyth in his 1913 treatise on

San Diego and Imperial counties. “He has been one of the greatest individual forces

in the development and progress of cattle raising and selling in San Diego

county and from prominence in one line of occupation has expanded his interests

to include the broader phases of municipal, commercial and political growth. He

was born in Martinez, Contra Costa county, California, and is the son of Isaac

Hardy, who came to the state in the early [18]50s."[xxxii]

Hardy “was a power in [Republican]

politics in San Diego from 1886 to 1909,” the Los Angeles Times later

recalled, “though he never held public office."[xxxiii]

The Fresno Republican referred to him as having been an "old time

political boss… His influence was felt, not only in San Diego County, where he

was influential in the construction of the first highways, but was extended throughout

the state, especially while J. N. Gillett was governor [1907-1911]."[xxxiv]

(In 1930 Hardy would sell his Bay City Market and presumably his associated meat

packing plant, for over a million dollars while still retaining another

$500,000-worth of local property for himself.)

Hardy had long been a close friend

and business associate of the O’Neills[xxxv]

and was still among the best-connected men and savviest businessmen in the region

when Jerome O’Neill died in 1926. The Santa Margarita’s heirs called upon Hardy

to take over as ranch manager and he accepted. Little did he realize that his

greatest challenge in the job would be facing off against his fellow Republican

politico and roads advocate, Col. Ed Fletcher.

|

| This photo of Charles S. Hardy appears in Ed Fletcher's memoirs. |

In response to Fletcher’s initial

claims about the ranch’s tax valuation, Hardy said that the ranch's assessed

value had long been set far too high. The Board of Supervisors ignored

Hardy, but he would continue to fight for the lowering of the ranch's taxes

until literally his dying day.

On June 30, 1930, Fletcher wrote a

letter to Hardy which read, in part,

I have been informed that offers

are being considered for the Santa Margarita Ranch.

I have a client who has authorized

me to make a definite offer of $10,500,000 for the Ranch including the holdings

outside the ranch, stock, personal property and crops.

This offer is $100,000 as option money

for ninety days from date, $1,900,000 within ninety days from expiration of

option with a trust deed at that time and deferred payments as follows:

$1,500,000 within two years thereafter;

$1,500,000 in four years, $1,500,000 in six years, $2,000,000 in eight years;

$2,000,000 in ten years with a reasonable release clause, taxes to be pro-rated,

possession to be given when the two million is paid…

If you will make a reasonable discount

for all cash, it is possible I can put thru a cash transaction.

I would appreciate a reply within

one week from date.

Hardy's reply, on July 7, was

cautiously worded. It read, in part,

In view of many circumstances well

known and not necessarily to be recounted, I cannot believe your letter to be

bona fide, but I lay that on one side and reply as though it were.

It is my opinion that the owners

of the Ranch (who speak for themselves) do not desire to sell the same, but if it

can command the price named by you their disposition might well be expected to be

otherwise; but even if they desired to sell, they would not (in my opinion)

consider any proposal made on behalf of an undisclosed principal.

If (a) you will name your client;

and if (b) he is fully able to carry through the purchase of the ranch at the

price named by you; and (c) to pay therefore in cash; and if (d) the offer

seems the property and without ulterior purpose, I feel certain that the owners

of the ranch (who, as I stated speak for themselves) will entertain the proposal,

and be quite willing to sell.

The owners, however (so I think)

will not give any option and will not string out payments on purchase price at

all, and certainly not to the unreasonable lengths named by you.

If your client (upon his identity being

disclosed) should seem to be abundantly responsible and beyond all doubt able

to finance the purchase, the owners might be willing to accept half the

purchase price in cash and leave the balance for a reasonable time secured by

deed of trust, without any release clause.

|

| Cattle ranching in south Orange County. (Courtesy OCA) |

Fletcher responded on July 8th:

My dear Mr. Hardy:

Answering your insulting letter of

July seventh, will say, my client made a bona fide offer, a reasonable

proposition with a reasonable payment of option money and reasonable payments of

principal, considering financial conditions today.

In fact, the terms of sale are

better than the average sales made last year of real estate in San Diego

County.

I question your sincerity and desire

to sell under any conditions.

I was simply working for the usual

commission in the sale of a piece of real estate. I have been working on this

prospect for months.

I have never been able to get, at

any time, a price from the owners of the Santa Margarita Ranch at which they

are willing to sell.

My client made you a legitimate

business-like offer. There was absolutely no ulterior purpose thought of.

If the owners or you as their

representative will agree to sell the property mentioned in my letter of the thirtieth

for $10,500,000, 25% cash, 25% in two years and the balance in six and you pay

me the usual commission for putting the deal over with 6% on the deferred

payments and a reasonable release clause, you to retain the ownership of the stock

during the two-year period until 50% has been paid, any monies taken in for the

sale of stock to be applied on payment of principal.

I believe a plan can be worked out

along these lines that will be mutually satisfactory and acceptable to my

client.

If you can give me something

definite to work on I would appreciate it and can give you a definite answer one

way or the other within ten days from date.

To Hardy’s irritation, Fletcher still

would not reveal the name of his client. But Fletcher continued to move ahead

as though a deal was possible. In October, Fletcher was still gathering as much

information on the ranch as he could find, hoping to broker its sale to his

"mystery client."

|

| Capone was at the height of his celebrity in 1930, when Time Magazine featured him on their cover. |

Notable among Fletcher’s papers is

his underlining of paragraphs citing the ease of transportation from the coast,

the many areas of the ranch that lent themselves to the landing of commercial and

private aircraft, the idyllic conditions for building luxury estates in

outlying "rural sections," and the ranch’s direct link to the Roosevelt

Highway (Pacific Coast Highway) which led to both Canada and Mexico. [xxxvi]

If, as it seems, Fletcher was

fully aware of the identity of his client, it was not in keeping with his image

as a “booster” who wanted the best for San Diego County. However, a sizable

commission on a $10.5 million transaction (more than $188 million in 2023 dollars)

and the favor of one of America’s richest men were incentives that would have

been hard to ignore.

Meanwhile, the people of Orange

and San Diego Counties seemed largely oblivious to the whole situation or at

least weren’t taking stories about Capone’s California ventures very seriously.

On Nov. 2, 1930, the Santa Ana

Register ran a front-page editorial promoting a local "dry"

candidate in the impending election. Ironically, it included the following

line: "If William Randolph Hearst, the outstanding leader of the 'wet'

forces,… and Scarface Al Capone of the Chicago gangsters and all who follow in

their train were in Orange County next Tuesday, there would not be one of them

vote for Harry C. Westover for District Attorney..."[xxxvii]

Little did they know that Capone was indeed already packing his bags for

another trip to Southern California.

Capone returned in Los Angeles

under an assumed name on November 9th. The LAPD knew he was in the

area, but admitted they didn’t know exactly where. Capone reportedly hung

around Los Angeles for about a week and then was seen in Santa Barbara and finally

Hollywood. [xxxviii] Rumors

later circulated that Capone had been offered a million dollars by a movie

studio to appear in a film, but he said there was “no deal on for a picture.” [xxxix]

Famed humorist Will Rogers observed, "They say Al

Capone is here in Los Angeles. Guess he is figuring on opening a western branch

here. This branch idea has just got this country by the nape of the neck. Now it

looks like the little home talent bootlegger who lived among us, raised his family

and paid his taxes, is to go the way of the local banker and little grocery

man. There is no chance for personal initiative any more; we are all just a cog

in a big machine that's controlled from New York or Chicago."[xl]

|

| Al Capone, 1931. |

Meanwhile, Ed Fletcher continued his

efforts on Capone’s behalf. Like Hardy, Hugh Evans & Company – the Los

Angeles investment realty firm which had an exclusive brokerage contract on the

Rancho – also demanded the identity of Fletcher’s client before they would do any

business with him. In a letter to Fletcher on Nov. 20, 1930, the very cordial Walter

D. Smyth of Hugh Evans & Co. wrote:

"...To avoid confusion or duplication

of effort, we ask that you register with the writer the names of such

prospective purchasers as you wish regarded as your clients. We feel a deal of

this magnitude calls for frank cooperation -- and ‘all our cards on the table.’

Even if we have had prior contact with your clients, (proof of which is subject

to your demand), we shall be only too glad to permit you to represent them

wherein the contract you have surpasses ours."

By Nov. 20th, there were rumors in San Francisco

that Capone had come up to the Bay Area on business and that he was “was planning

a palatial home in the millionaire colony of Montecito” near Santa Barbara, “and

that several reputed henchmen were looking over possible sites for a 'winter estate.'" [xli]

While playing horseshoes at another ranch somewhere in

Southern California on November 23rd, Capone entertained reporters.

He’d given up all pretense of hiding his identity, but was still cagey.

"Don't make public where this ranch is located," he told them. Among

other things, he told the newsmen that he planned to buy some California real

estate. Capone sightings had been reported in both Santa Barbara and Hollywood in

the prior week. [xlii]

In late January 1931, the LAPD made

the shocking but rather undetailed revelation that agents for Capone had been trying

to buy the Rancho Santa Margarita. [xliii]

In the Los Angeles Times, Orange County historian and former Santa Ana Register publisher Terry E.

Stephenson wrote, “The fact that the old ranch has thirty-five miles of coast

line where bootleg booze could be landed in secret may not have escaped the innocent

gang Napoleon.” [xliv]

|

| Map from L.A. Times profile on local rum-running operations. Aug. 8, 1926 |

In fact, this lightly patrolled section of the coast was

already an extremely popular landing spot for rum running boats from Mexico [xlv] or from large smuggling ships anchored several miles out in international waters. There

was not much the authorities could do about it. This contraband was headed for

Los Angeles or other cities. Most of the locals’ supply in southern Orange

County was actually booze stolen from these shipments. [xlvi]

Throughout Prohibition, the closest

thing Southern California had to a “mob” directing bootlegging was a consortium

of the LAPD, politicians, prosecutors and criminals like rumrunner Tony Cornero.[xlvii]

But this consortium wasn’t nearly as powerful or far-reaching as Capone’s Outfit

or the New York mob. Most Southern California bootleggers were just “individuals

trying to bring in extra cash,” writes Southern California organized crime

historian Richard Warner. “Most of the big bootleggers worked together or

respected [each other’s] territories.” [xlviii]

|

| Boat wrecked at Salt Creek Beach during attempted night delivery of 200 cases of whiskey, 1932. (Courtesy First American Title Co.) |

Historian Pamela Hallan-Gibson related

that deliveries of contraband liquor were hidden in a variety of spots on or

near the Rancho Santa Margarita, including under the sand of dry creek beds and

what’s now the Del Obispo St. bridge over Trabuco Creek. “Once a local found

some hooch hidden on the Santa Margarita Ranch property,” she wrote. “Instead of

stealing it all, he took what he needed, one bottle at a time. The owners [of

the booze], who were not locals, discovered the theft and didn’t take too

kindly to it. They confronted the thief with machine guns and persuaded him

that it would be unhealthy for him to take any more.”

|

| Orange County Sheriff Sam Jernigan and his men dump confiscated hootch down manholes at the County's Fruit Street Yard, Santa Ana, Mar. 32. 1932. WCTU representatives look on. (Courtesy OCA) |

In another incident, a hunter traversing

the brush near San Onofre stumbled upon a well-dressed man with the top of his

head shot off. The unfortunate man was clutching a shotgun with one expended shell,

had a fake license in his pocket, and had been dead about a month. Officers

believed he’d been killed by the rum runners known to use the coast near San

Onofre and San Mateo Creek.

[xlix]

As a base of operations for bootlegging and other criminal

activities, the ranch was comfortably remote, yet conveniently located. It was

within easy reach of boats from Mexico and a relatively short drive from Los

Angeles. And if things got hot, it was a short run to the border.

|

| Map of Rancho Santa Margarita with Capone, Los Angeles Times, Mar. 22, 1931 |

Stephenson described the ranch as “so vast that Al Capone

could drop his beloved city of Chicago in the middle of it and all around would

be a wide fringe of cactus and sagebrush in which coyotes and wildcats roam and

in which Capone could put machine guns enough to hold off all the police in the

world.” [l]

In a May1931 article in the

national Liberty magazine, well-known

writer Homer Croy brought much more public attention the LAPD’s claim. He playfully

mixed Chicago mob cliches with old “romance of the ranchos” cliches. And he cheekily

added that Capone wanted to move to Southern California because Chicago winters

wreaked havoc on his “delicate throat” and because his 17-room Florida home was

too small.

Others mused that Capone may have wanted to retire from his

life of crime.

"In the old days robber chieftains often retired... to

placidity under the shadow of a country mansion," wrote one Iowa newspaper

editor. "Will we, do you suppose, yet see the underworld king of Chicago

living out a life of peace on a somnolent country estate?"[li]

Echoing that thought, the gangster’s grandniece, author and

family historian Deirdre Capone writes, “My grandfather Ralph and my Uncle Al

were looking at ranches but not for landing his boats. They wanted out of the

liquor business and were looking at the movie industry and raising horses.”[lii]

|

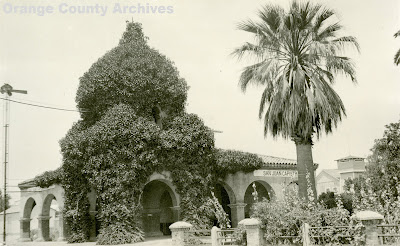

| Mission San Juan Capistrano, circa late 1920s (Courtesy OCA) |

But the prevailing belief was that Al Capone was still up to

no good, and the possibility of having him as a neighbor generated a lot of agitation

and discussion in San Juan Capistrano – located in the heart of the ranch. Citizens

were afraid that their sleepy mission town might become the site of gangster

shootouts. Some of the war veterans in the area semi-secretly formed an armed “committee

of vigilance” and made plans to snipe Scarface from the hilltops. [liii]

San Juan Capistrano in 1931 was struggling, like most

communities, with the effects of the Great Depression. But agriculture provided

most residents with at least some employment, which provided a bit of a buffer.

Small town life rolled along. The popular story of the swallows' annual return was

newly in circulation, community sports teams were popular, there was buzz about

a nearby lost gold mine, the crops got some decent rain on them, elections were

held for the Sanitary District board, and a new high school gym was under construction.

Life was pretty good in sunny San Juan Capistrano, and the residents wanted to

keep it that way. While there was certainly some demand for liquor in the town,

most was stolen in small amounts from bootleggers, not brought in and sold by

organized crime. Townsfolk were happy enough to see local rumrunners busted, like Henry D. Nidiffer, who was found with twenty-four

pints of whiskey in his Capistrano apartment. [liv]

The idea of a big-time criminal like Capone in their midst was an outrage.

|

| Oceanside, 1930s (Courtesy Pomona Public Library) |

By contrast, the response from the town of Oceanside – on the

rancho’s southern border – was quite different. Croy’s article was “interesting

from a fiction point of view," opined the Oceanside Blade-Tribune,

"and incidentally carries some good publicity for this section, as the

[accompanying] map shows the San Luis Rey Mission and shows Oceanside's

relative position to the rancho." [lv]

Shortly after Croy’s article hit the newsstands, Hardy –

echoing his correspondence with Fletcher – publicly denied reports that Capone

had already purchased the property. [lvi] [lvii]

“Whoever buys this ranch, if it is ever sold, will have to

show who he is and what he is going to do with it,” Hardy told reporters. “The

owners of this property realize their obligations to California. Al Capone could

not buy it if he had the necessary money."[lviii]

But then Hardy went on to deny that the gangster had even

shown an interest in the ranch, calling such stories “bosh.” [lix]

|

| Al Capone, circa 1935 (FBI photo) |

“I am positive,” Hardy said, “that neither Capone nor any of

his men nor anyone representing him has ever made any overtures to purchase the

holdings. I doubt very much that any of the Chicago gangsters ever heard of the

ranch, much less started an attempt to purchase it.” [lx]

In a 1977 Register article, retired Orange County

Sheriff’s Department Investigator Dan Rios – who was in San Juan Capistrano in early

1930s – said Capone’s attempted purchase of the rancho “was a fact” that had

been hushed up. Capone, Rios said, was “pretty subtle about his move and he had

an agency helping him to buy the ranch. But it came out anyway.” Rios said the

O’Neill and Flood families, at the time of the attempted purchase, only dealt

with agents and never knew who was actually making these bids to buy the ranch. [lxi]

The attempted purchase died aborning, although reports

varied as to why. Columnist

Harry Carr thought it was San Juan’s vigilantes who scared off Capone and ended

his "yen to be a California hacendado."[lxii]

Deputy Rios thought Capone was pushed out because “the syndicate

in Hollywood which ran the bootlegging operations along the coast didn’t want

the competition… The Los Angeles police rumored to be involved with the local

syndicate blocked the deal. After the smoke cleared, several officers left in a

hurry for Mexico.”

|

| James "Two-Gun" Davis served as Chief of the LAPD from 1926 to 1929 and 1933 to 1939. (Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library) |

Indeed, if anyone could have forcibly

put a stop to a West Coast expansion by Capone, it would have been the LAPD and

their criminal allies. [lxiii]

But ultimately, Capone’s dreams of

ranch ownership were dashed, along with the rest of his plans, when he was

indicted on charges of income tax evasion and violating the Volstead Act

(i.e., Prohibition) in June of 1931. In late

November he was given an eleven-year sentence, which – combined with his

declining health – effectively ended his criminal career.

|

| Al Capone, 1931 (Chicago Detective Bureau photo) |

Even with Capone behind bars, the story of his interest in the

ranch lived on. Robert E. Neeley of the IRS was put in charge of finding the

gangster’s hidden stashes of loot, from coast to coast. Neeley incorrectly told

the press that in addition to Capone’s property in Chicago, Miami, and Wisconsin,

he also owned “the huge Santa Margarita Ranch, including thirty-five miles of

ocean front between Los Angeles and San Diego…” [lxiv]

Neeley’s confusion was understandable. Capone’s financial

transactions were intentionally murky. Internal Revenue Agent W.C. Hodgins,

who’d originally led the team investigating Capone, wrote a letter to his

superiors earlier in 1931, emphasizing the near impossibility of cracking

Capone’s shrewd and secretive dealings to determine what the kingpin actually

owned. “Al Capone never had a bank account and only on one occasion could it be

found where he ever endorsed a check, all of his financial transactions being

made in currency,” wrote Hodgins. “Agents were unable to find where he had ever

purchased any securities, therefore, any evidence secured had to be developed

through the testimony of associates or others, which, through fear of personal

injury, or loyalty, was most difficult to obtain.” [lxv]

For some years, not much changed. Cattle

continued grazing in the hills of the Rancho Santa Margarita. Capone sat in his

cell. And a bit of smuggling continued on the remote beaches even after the 1933

repeal of prohibition. Booze from Mexico, sans tariffs, remained profitable.

|

| Cattle on Rancho Santa Margarita (Calif. Historical Society Collection, USC Libraries) |

Perhaps tellingly, Ed Fletcher’s fervent

interest in defending and further promoting the raising of property taxes on

the Rancho Santa Margarita seemed to fade dramatically just as Capone went to

prison. After more than two years of taking every opportunity to promote this

cause, Fletcher seems to have dropped the subject entirely – his last minor effort

being made as one among many witnesses at a September 1931 trial regarding the accuracy

of the ranch’s assessed value.[lxvi]

By the late 1930s, the Floods and their kin, the Baumgartners,

still wanted to sell the ranch, but the O’Neills wanted to keep it.[lxvii]

So in 1939, they split up the ranch, setting its fate once and for all. The Floods

and Baumgartners got the southern portion –

the old Rancho Santa Margarita y las Flores – which the Federal government acquired

only a few years later to create Camp Pendleton. The O’Neill family got the

northern portion, to which they applied the old historic name of Rancho Mission

Viejo.

|

| 9th Marine Regiment marches into the new Camp Pendleton, Sept. 1942 (Dept. of Defense photo) |

Rumors of Capone’s attempted purchase of the ranch continued

to circulate for over ninety years, primarily fueled by Croy’s feature article.

Most, including most historians, doubted the tale because little convincing

evidence had yet been uncovered, much less arranged in such a way as to establish a potentially convincing chain of events.

|

| Sensationalized "true crime" magazine, 1931. |

Adding more reason for skepticism,

seemingly every corner of North America – from Amityville, New York to Baja

California – invented its own stories about Capone having a secret home,

business venture or hideout nearby. For instance, Capone supposedly worked as an

honest bookkeeper in Baltimore before leaving for Chicago to work for his mob mentor,

Johnny Torrio.[lxviii]

Another false account had Capone owning a home in Cuba. Even Moose Jaw,

Saskatchewan developed a myth in the 1990s that tunnels under their town were once

the backbone of major criminal operations overseen by Capone himself.[lxix]

When the veracity of the Moose Jaw story was questioned, tunnels were quickly

dug to feed the tourist trade, solidifying Capone as the town’s new mascot.[lxx]

[lxxi]

The difference between these many

myths and the Rancho Santa Margarita story is that actual evidence has now been

identified that Capone made a serious effort to acquire the rancho. [lxxii]

Ultimately, however, neither the machinations of Chicago’s malevolent

“Beer King,” nor the punitive taxes promoted by Ed Fletcher would have their

intended effect. [lxxiii] The

southern portion of the rancho became Camp Pendleton and the northern portion paid

off as part of the biggest Southern California racket of all: real estate.

|

| Grading land for housing tracts, Mission Viejo area, 1985. (Courtesy OCA) |

Having avoided becoming part of Capone’s alcohol-fueled

empire of vice, much of the ranch was developed, beginning in the mid-1960s, into master-planned communities

the City of Mission Viejo, the City of Rancho Santa Margarita, Las Flores, and Ladera Ranch. The developer was

the Mission Viejo Company, which by then was a division of tobacco company

Phillip Morris and operated – ironically enough – under the auspices of their

Miller Brewing Co.

--- --- ---

Acknowledgements:

Over the twelve years of my periodically picking away at

this article, I’ve had a lot of help from others who provided good leads,

suggestions, background information, insights, constructive criticism, and access to important

materials. My thanks to Tony Moiso and Emmy Lou Jolly-Vann of the Rancho Mission

Viejo, to Camp Pendleton Historian Faye A. Jonason, to historian Richard

Warner, to (now retired) California State Parks historian Jim Newland, to Jan Siegel of the San Juan Capistrano Historical Society, to Karen

Wall of the Orange County Public Library, to museum curator Jennifer Ring of

Mission San Juan Capistrano, to author/historian Pamela Hallan-Gibson, and to archivist

Fr. William Krekelberg and his successor Fr. Chris Heath of the Diocese of

Orange. And even greater thanks and love to fellow Orange County historians Stephanie

George, Eric Plunkett, and the late great Jim Sleeper and Phil Brigandi.

[i] “Don Juan Forster,” San Juan Capistrano Historical Society website. Apr. 13, 2021. Accessed 1/14/2023.

[ii] Forster

also owned the smaller Potrero Los Pinos in Orange County’s mountains, and the

Potrero El Cariso and Potrero De La Cienega in Riverside County.

[iii] Stephenson,

Shirley E. John J. Baumgarner, Jr.:

Reflections of a Scion of the Rancho Santa Margarita, California State University

Fullerton Oral History Program, 1982.

[iv]

Schoenberg, Robert J. Mr Capone, William Morrow & Co., Inc., 1992.

[v] "Chicago

Gangster in Los Angeles," United Press, Dec. 13, 1927

[vi] "Scarface

Al in San Diego," United Press, Dec. 10, 1927

[vii] "Scarface

Al Mighty Glad to be Home," United Press/Wisconsin State Journal, Dec. 17,

1927

[viii] Journalist

Maya Kroth went to Tijuana searching for proof that Capone had visited. The

closest she got was a book, Panorama Histórico de Baja California

(1982), in which Elena de la Paz de Barrón -- once a coat-check girl at the

Agua Caliente casino -- claimed Capone had tunnels under the resort for

smuggling liquor. But Kroth learned that the tunnels were for the resort's underground

water and electrical ducts,. (Kroth, Maya. “In Tijuana, Searching for Al

Capone,” Washington Post, 12-31-2014)

[ix] Mission Guest Register Feb. 28, 1927-Feb. 5, 1934, Mission

San Juan Capistrano (Corroborated by Carr, 1934)

[x] E-mail correspondence

to author from Karvelis’ relative and genealogist Bonny Albrecht, 2/26/2023. Albrecht

describes asking Marion’s sister, Stella Karvelis, about the friendship with

Capone. “My aunt Stella (would always change the subject) saying ‘Marion had many

friends and when a taxicab had taken her home early one morning after work and

had an accident and Marion was hospitalized the Marx Brothers sent her a large

fruit basket to the hospital.’ Marion lived with her parents and siblings in an

area of Chicago called Garden Homes, less than three miles from Capone’s house.

Capone, writes Albrecht, “would come to the Karvelis home and would sometimes play

baseball with the men living in Garden Homes or sometimes just send a car for

Marion. …Marion later worked at the Chez Paree Theater Restaurant / Nightclub

in Chicago with many headliners, including Bob Hope, Sophie Tucker,” and Fred

Astaire.” Also see Capone, Diane Patricia, Al Capone: Stories My Grandmother

Told Me, 2019, which describes Al’s wife, Mae, learning about a blonde Al

had been seeing. She retaliated by driving his new Cadillac into a building.

But then Mae went and had her dark hair dyed blonde. The author wonders if the unknown blonde in question was Karvelis.

[xi] Marion Karvelis

– born Marianna S. Karwjalis in Latvia – would not become a U.S. citizen until

1937. (U.S. Naturalization Record Indexes, Northern District, Illinois,

1926-1979)

[xii] Carr got

some details wrong, including suggesting that the visit took place around 1931 or

1932.

[xiii] In correspondence

with the author via Ancestry.com on Jan. 28, 2023, Bonny Albrecht stated that “Marion

Karvelis was a friend of Al Capone.”

[xiv] The

Roman Catholic Diocese of Owensboro Kentucky, Turner Publishing Co., 1994

[xv] Early

California historian Eric Plunkett – Telephone conversation with the author, Feb.

11, 2023.

[xvii] Brown

became a local legend for throwing Capone out of Los Angeles. Brown was later

arrested and temporarily thrown off the force for extorting and accepting

bribes from bootleggers. (See "Roughhouse to Trial Again" Los

Angeles Evening Express, Jan. 31, 1930. Also "3 Ex-Cops Fate to Jury

Today," Los Angeles Evening Express, Nov. 18.1929) LAPD Officer William J. "Sledgehammer" Jolin -- who was busted in the same bribery case and also had a track record of brutality -- claimed to have been Brown's partner in throwing Capone out of L.A. "We told Capone his vacation was over," Jolin recalled upon his retirement in 1944. "Al says, 'O.K., boys, let's go.' We walked him down to the station." (See "Policeman Who Ran Al Capone Out of City in 1929 to Retire," Los Angeles Times, May 12, 1944.)

[xviii] "Los

Angeles Fires Scarface Al," Associated Press, Dec. 13, 1927

[xix] "Request

Capone to Leave Los Angeles," United Press, Dec. 13, 1927

[xx] Daniell,

J. B. "Comment," Venice Evening Vanguard, Dec. 14, 1927

[xxi] "Chicago

Cops Await Return of Al Capone," United Press, Dec. 16, 1927

[xxii] "'Scarface

Al' Came to Play, Now Look --- He's Gone Away!," Los Angeles Times, Dec.

14, 1927

[xxiii] There’s

doubt as to whether Capone primarily wanted to secure a cut of the local

rackets in St. Petersburg, if his investment was made as a favor to Torrio (who

moved to the area), if it was just legitimate land speculation, or if it was a

way to launder money. In any case, Capone was only ever in St. Petersburg himself

once, for a few hours.

[xxiv] Michaels,

Will. "A New Look at Al Capone in St. Pete," Northeast Journal, (Part 1 and Part 2), 2015

[xxv] "Gangs

Said to Plan Big Dope Ring in L.A. Region," Sacramento Bee, Jan.

28.1931. (Note: Other newspaper

accounts cite the offer of a certified check for $50,000 rather than $200,000.)

[xxvi] “Capone Seeks to Buy Orange County

Ranch,” Santa Ana Register, Jan. 28, 1931.

[xxvii] "Biography,"

finding aid, Ed Fletcher Papers, San Diego State University Library Special

Collections

[xxviii] "Stormy

Meeting on Tax Matter." Daily Times-Advocate [Escondido], Jul. 10,

1929.

[xxix] “Sets

10 Million as Ranch Value." Daily Times-Advocate [Escondido], Jul.

15, 1929

[xxx] “Santa

Margarita Value is Raised." Daily Times-Advocate [Escondido], Jul.

16, 1929.

[xxxi] "South

of the Tehachapi." Los Angeles Times, Nov. 16, 1908

[xxxii] Smythe,

William Ellsworth. San Diego and Imperial Counties, California: A Record of

Settlement, Organization, Progress and Achievement, Vol. 2, S.J. Clarke Publishing

Co., New York, 1913

[xxxiii] "Heart

Attack Takes Rancher." Los Angeles Times, Jul. 14, 1931.

[xxxiv] "C.

S. Hardy, Meat Packer, Cattleman, Dies in San Diego." Fresno Morning Republican,

Jul. 14, 1931.

[xxxv] "Complete

Chronicle of One Day’s Doings South of the Tehachapi." Los Angeles

Times, May 10, 1910.

[xxxvi] "Rancho Santa Margarite Y Las Flores Rancho" (draft

prospectus), Allen & Company Realtors, Oct. 1930, Box 67, Folder 1, Ed Fletcher

Papers, San Diego State University Library Special Collections

[xxxvii] "The

Real Fight in Orange County," Santa Ana Register, Nov. 2, 1930

[xxxviii]

"Tracking Capone," Lebanon [Pennsylvania]

Semi-Weekly News, Nov. 13, 1930. (AP

story)

[xxxix] "Fitts

Threatens 'Al' But Gets Laugh from Chicago Gangster," Lubbock [Texas] Morning Avalanche,

March 31, 1931 (AP story)

[xl] Rogers,

Will. "Will Rogers Remarks," Los Angeles Times, Nov. 14, 1930

[xli] "Things

Wise and Otherwise by A.P.B.," Santa Maria Times, Nov. 22, 1930

[xlii]

"Capone Pitches Horseshoes, Chats with Reports About Surrendering," Decatur [Illinois] Evening Herald, Nov. 24, 1930. (United Press story)

[xliv]

Stephenson, T. E., “The Ranch Al Capone Wants to Buy.” Los Angeles Times, March 22, 1931.

[xlv] San Diego Union, June 9, 1968.

[xlvi] Hallan,

Pamela. Dos Cientos Anos en San Juan

Capistrano, Lehmann Publishing, 1975.

[xlvii] Holland, Gale. "A Bit of Digging Unearths Tales

of L.A. Bootlegging, Crooked Cops," Los

Angeles Times, Oct. 11, 2012.

[xlix] “Body

of Man is Found by Hunter,” Santa Ana Register,

Feb. 29, 1932.

[l] Oddly enough,

Al Capone’s estranged older brother, James, would have been a lot more at home

on a ranch than his Chicago brothers. James changed his name to Richard James

Hart, in honor of movie cowboy William S. Hart, and served as a lawman (and prohibition

agent!) in small towns and Indian reservations “out west.” He learned the

Indian languages, wore cowboy hats and western boots, and earned the nickname

“Two-Gun Hart” for his sharpshooting and his pearl-handled revolvers.

[li] "Gentleman

Gangsters," Ames [Iowa] Daily Tribune-Times, April 3, 1931.

[lii] Email

from Deirdre Capone to Chris Jepsen, May 2, 2011.

[liii] Carr,

Harry, “The Lancer.” Los Angeles Times,

July 24, 1932.

[liv] “County

Constables Arrest Seven in Liquor Raids,” Santa

Ana Register, July 20, 1931.

[lv] "Enters

Denial of Rancho Sale." Daily Times-Advocate [Escondido], June 8,

1931.

[lvi] Hardy

died less than two months later of a heart attack. He’d been the ranch manager

for six years. In announcing his death, the

Santa Ana Register (July 15, 1931) described Hardy thusly: “Ruggedly honest,

just in his dealing, he was the typical American who has won his way from poverty

to the millionaire class.” They cited Hardy’s insistence that newspapers

(nationwide) print his denial of the Capone ranch purchase as an example of his

dedication to the truth.

[lvii] "Capone

Deal Denied," Oakland [California]

Tribune, May 29, 1931.

[lviii] "Orange

County, Southland Mourns Death of Business Leader Charles S. Hardy," Santa Ana Register, July 15, 1931.

[lix] “Hardy

Denies Purchase of Margarita Ranch by Capone,…” San Diego Evening Tribune, May 28, 1931.

[lx] "Heavily

Armed Deputies Follow Trail in Search of Desperadoes Linked to

Kidnapping." Los Angeles Times,

January 29, 1931.

[lxi] Wulff,

Stan, “Capone’s Offer for Ranch in South Orange County Refused,” Register, January 2, 1977.

[lxiii] Warner,

Richard. Feb. 1, 2023

[lxiv] “New

Capone Search On,” Los Angeles Times,

June 8, 1931.

[lxv] Letter dated July 8, 1931, from Internal Revenue Agents W.C. Hodgins, Jacque L. Westrich,

and H.N. Clagett to the Internal Revenue Agent in Charge, Chicago, Illinois.

[lxvi] “Many

Are Heard in Rancho Action.” Weekly Times-Advocate [Escondido], Sept. 25, 1931

[lxvii]

Stephenson, Shirley E., pg 29.

[lxxii] Warner,

Richard. Email correspondence with author. Mar. 7, 2023. (A reference to the evidence uncovered by this article.)

[lxxiii]

Ironically, in the mid-twentieth century new property tax rules punishing

agriculture and promoting development all but forced the O’Neills to gradually

sell or develop much of the northern portion of the Rancho Santa Margarita.