|

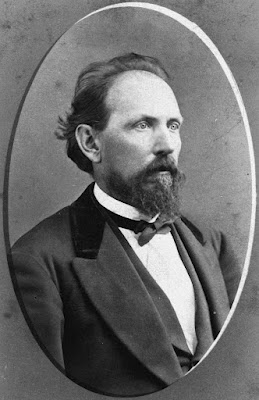

| John H. & Johanna Lütgens (Courtesy thoneybourne on Ancestry.com) |

Anaheim, Orange County’s first incorporated city and one of California’s first “planned communities,” was actually born in San Francisco. Specifically, it was planned, named, and financially supported at meetings held at John Lütgens’ Hotel, on Montgomery St. across from the Russ House in what’s now the Financial District. Lütgens’ Hotel, as the San Francisco Chronicle later recalled, “was the favorite lodging-house of the better class of Germans.” And that – along with a smattering of immigrants from other European countries – is exactly who created Anaheim. Likewise, their host, hotelier John Henry (Johan Heinrich) Christian Lütgens had been born in Kiel, Germany in 1816 and was naturalized in San Francisco in 1856 – at the end of the California Gold Rush.

The story of Anaheim's founding has been told many times before (including solid accounts from historian Leo J. Friis). But seldom, if ever, has Anaheim's actual birthplace been put in the spotlight.

|

| Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. map, 1887, showing Lütgens’ Hotel. |

The concept of Anaheim began when Los Angeles vintner John Fröhling and his San Francisco distributor, Charles Kohler, needed a more reliable supply of wine to sell. The two men, along with fellow German immigrant and wine dealer Otto Weyse, imagined a new cooperative vineyard colony in Southern California. They quickly enlisted Austrian-born surveyor and civil engineer George Hansen of Los Angeles. They made attorney Otmar Caler president of a group – composed primarily of other Bay Area Germans -- that would further organize and promote the colony. They called an organizational meeting for February 24, 1857 at Lütgens’ Hotel, during which they agreed to incorporate as the Los Angeles Vineyard Society. They also made Hansen superintendent and sent him south to find, purchase and prepare an appropriate piece of land.

|

| Seal of the Los Angeles Vineyard Society. (Courtesy Anaheim Public Library) |

Four days after the organizational meeting, a second meeting was held at which officers and directors were chosen and twenty-seven shares of stock were sold at $250 each. Those who bought share were, again, mainly prominent Germans in the San Francisco area. The expense of the stock was somewhat hidden, as the investors each had to kick in the difference each time the stock prices were raised.

From then on, monthly Board of Directors meetings were held at the hotel, always beginning promptly at 8:00 p.m. At the March 2, 1857 meeting, they appointed a finance committee.

The board of the Vineyard Society included many (now) well known Anaheim pioneers. It also included John Lütgens.

|

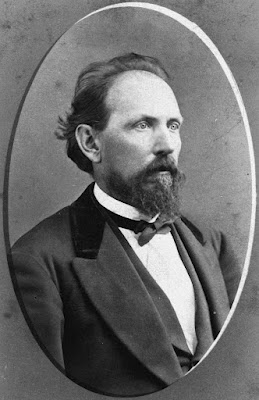

| George Hansen, father of Anaheim (Courtesy Anaheim Public Library) |

By April, George Hansen was trying to cut deals with various major property owners in Southern California and was sending progress reports back to the board. After several false starts, Hansen found a good spot on the Rancho San Juan Cajon de Santa Ana and found a willing seller in rancho owner Juan Pacifico Ontiveros who was looking to move north to the Santa Maria area. (Hansen knew the Ontiveros family, as he had surveyed their land a few years earlier.) Pending reimbursement by the Society, Frohling and Hansen paid Ontiveros, out of their own pockets, two dollars an acre for 1,165 acres.

|

| Don Juan Pacifico Ontiveros. (Courtesy Anaheim Public Library) |

During the Jan. 13th, 1858 Society meeting at Lütgens’, members voted to give their colony the name Annaheim. (Later, the second “n” was dropped.) The moniker referenced their new home (“heim” in German) on the Santa Ana River and in the Santa Ana Valley. The name beat out two contenders: Annagau and Weinheim. Board member Theodore E. Schmidt likely suggested the winning name. At this meeting they also voted to increase their cumulative stock value to $50,000 as soon as the State Legislature amended the Incorporation Act to allow agricultural companies to incorporate.

State Senator (and former Los Angeles mayor) Cameron E. Thom submitting just such an amendment to the legislature in 1859. The measure was opposed by some who feared large corporations would eventually accumulate huge areas of real estate. (The Daily Alta California opined that "this fear is an absurd one.") But a version of the bill amending the Incorporation Act ultimately became law.

|

| Cameron E. Thom. (Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library) |

On October 2, 1858, the following paid notice was printed in the Los Angeles Star:

"The members of the Los Angeles Vineyard Society are hereby notified by the undersigned, constituting a majority of the Board of Trustees thereof, that a meeting of the Stockholders will be held in this city [San Francisco], on Saturday Evening, October 23, 1858, at Lütgens' Hotel on Montgomery Street between Pine and Bush streets, for the object of increasing the Capital Stock of said Company to Sixty Thousand dollars... or each share to One Thousand Two Hundred Dollars...

C. C. KUCHEL, President

T. E. SCHMIDT

HUGO SCHENK

RUD LUEDKE

JOHN LÜTGENS

H. BREMERMAN

J HARTMAN

JOHN BACH

H. PODDERATZ

JOHN P. ZEYN

JOHN FISCHER, Secretary

San Francisco, Cal... 1858"

At a general meeting on February 28, 1859, fifty building parcels in the center of Anaheim were distributed to Society members by drawing lots, with another fourteen parcels held in reserve by the Society.

|

| Map of the Anaheim "Mother Colony." (Courtesy Anaheim Public Library) |

In advance of the arrival of the first colonists to Anaheim, later that year, Hansen began preparing the land for them. After obtaining rights to an easement across Bernardo Yorba’s adjacent ranch, Hansen built an irrigation ditch which brought water down from the river, and then laid out Anaheim on the same angle as the ditch. To this day, the heart of Anaheim still has this cockeyed orientation. Hansen divided the land into town lots and vineyard lots – all within the boundaries of North, South, East and West streets. He also oversaw the planting of 400,000 vines, as well as some fruit trees. Additionally, he planted willows all around the town’s perimeter, creating a living fence to keep out roaming animals. The “gates” in the fence along each side of town would become landmarks.

By early spring, the new ditch was bringing Santa Ana River water into town and Anaheim’s vineyards were a bustling hub of activity.

|

| Plat map of early Anaheim. (Courtesy Anaheim Public Library) |

On June 23, 1859, the Society held a dinner at Lütgens’ Hotel in honor of their surveyor and vineyard superintendent, George Hansen. He had worked hard for them in Anaheim for two years and this was his first trip back to San Francisco. Hansen addressed the Society, reviewed their own history, caught them up on progress, and told them that their first 400 acres of vineyards were already flourishing. Everyone had a grand time, wine flowed freely, and the party finally broke up in the wee small hours of the morning.

At the Society’s monthly meeting at the hotel on September 12, 1859 they voted to increase share prices to $1,840, “and to make a distribution of the Vineyard lots among the shareholders of the Association." More shareholders announced that they planned to move down to Anaheim soon and make their permanent homes there.

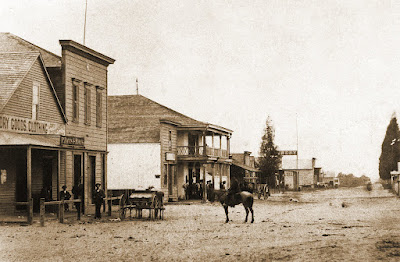

|

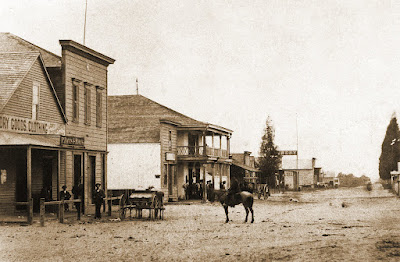

| West Center St. (now Lincoln Ave.), Downtown Anaheim, 1873. (Courtesy Anaheim Public Library) |

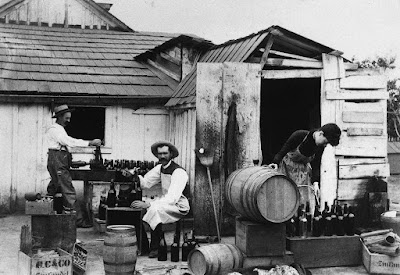

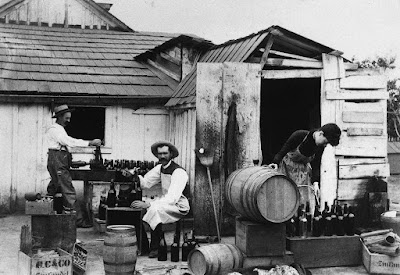

In December 1860, recognizing the colony’s rapid development, the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors ordered that a new Anaheim Township be carved out of the old Santa Ana Township. Anaheim was already a well-established community. While Pierce’s Disease would wipe out Anaheim’s wine grape industry in the 1880s, growers would turn to other crops, like walnuts and citrus, and Anaheim’s growth continued. Today, it’s an internationally famous city of 350,000 residents.

|

| Bottling wine at the Bullard Winery, Anaheim, circa 1885. (Courtesy Anaheim Public Library) |

Lütgens’ Hotel was sold later in the 1860s and torn down in 1891 to make way for the construction of the Mills Building on the same site. Darius Ogden Mills had previously founded the National Gold Bank of D.O. Mills & Co., (the first bank west of the Rocky Mountains) and later helped found the Bank of California. He hired architects Burnham and Root of Chicago to design his Mills Building.

|

| The author in front of the Mills Building, Thanksgiving, 2021. |

The steel-framed Mills Building survived the 1906 earthquake. Although the interior was damaged in the fire following the quake, it was restored to original condition in 1907. Today, the Mills Building is San Francisco’s last example of the “Chicago school” of architecture, which features Richardson Romanesque elements. In the case of the Mills Building, these elements include a dramatic entrance arch facing Montgomery Street. The 22-story Mills Tower was added in 1932.

|

| The staircase in the Montgomery St. lobby – made of French “Jaune Fleuri marble” – is original. |

In December 1868 – the same year in which his wife, Johanna, died -- John Lütgens opened a new Lütgens' Hotel with a partner, Mr. Lowrey (formerly of the Western House), on Post Street, above Kearny Street in San Francisco. Wine, of course, flowed freely at the grand opening.

|

| Interior view, Mills Building, 2021 (Photo by author) |

Perhaps inspired by memories of his old Vineyard Society friends, Lütgens spent a time as a liquor dealer later in life. In 1878, his liquor business was located at 233 Montgomery Ave. – just across the street from the original Lütgens’ Hotel. He died in San Francisco on June 23, 1899. Anaheim continued to flourish and has since largely forgotten John Lütgens and the exact location of its own birth.

|

| View up Montgomery St. from the site of the old Lütgens Hotel, 2021. (Photo by author) |

%20with%20host%20James%20Smith%20(right).jpg)

%20on%20display%20at%20the%20Old%20Courthouse%20in%202010%20-%20Photo%20by%20Chris%20Jepsen.jpg)

%20and%20friend,%20bear%20hunting,%20circa%201900%20-%20photo%20courtesy%20Orange%20County%20Archives.jpg)