|

| 1889 map of the newly formed Orange County. (Courtesy Library of Congress) |

How did Orange County get its name? There are many colorful, popular lies (myths?) in circulation that purport to answer that question. In fact, historian Phil Brigandi placed those myths at the very top of his list of the “six most common mistakes” made regarding Orange County history.

In just the past couple months, yet another wrong tale has been making the rounds: Someone suggested that “Orange” was a reference to the Orange Order of Ireland and thus was chosen as a message to Catholics that they were unwelcome here.

Even if we didn’t already know the real story behind the origins of county’s name, (and I'll get to that momentarily), this newly-constructed myth would be ridiculous on its face. The name “Orange County” was proposed in 1872 and put into use in 1889. Many, many Catholics already lived here. In fact, the first “outposts of civilization” here – San Juan Capistrano and Bernardo Yorba’s ranch headquarters – were anchored by Catholic places of worship and their population was almost exclusively Catholic.

So why and how did Orange County get its colorful name? Was it because of our many orange groves?

Nope. But that's certainly the most popular wrong answer.

No, the real story began in late 1869, when Anaheim mayor Max Strobel proposed a new “Anaheim County.” The effort failed, but it was only the first of many attempts to form a new county from the southern part of Los Angeles County.

The name “Orange County” was first proposed at an 1872 meeting of county secession proponents in what’s now Downey. At that time, southern Los Angeles County only had a few experimental orange trees and no citrus industry. Agriculture drove our economy, but the big money was in sheep, pigs and grapes. (Be glad we don’t live in Swine County.) As historian Jim Sleeper noted, the name Orange County was proposed “four years before our first Valencias went in the ground” and “two years before the village of Richland was renamed Orange.”

So, again, why Orange County?

|

| California citrus promotional items from the David Boulé collection. (Author's photo) |

The late 1800s and early 1900s were a period of “boosterism” in Southern California. We believed that the best way to improve our region and economy was to constantly trumpet our many positive traits and to encourage people to move here and do business here. A common theme in this cheerleading or “boosting” was that our rich soil and idyllic “semi-tropical” Mediterranean climate allowed nearly any crop to flourish here.

To Americans, oranges were still an exotic luxury. It was something special if Santa Claus left an orange in your stocking at Christmas. You might not see another one all year.

And in the minds of most Americans, this prized fruit was a symbol of warm, coastal, Mediterranean climes – especially sunny Spain. And hints of Spain, of course, were reminiscent of California’s colorful Rancho Era – a heavily sentimentalized and marketed chapter of our history. Romantic tales of Spanish and Mexican (and yes, as it happens, Catholic) California were a beloved part of the popular culture.

|

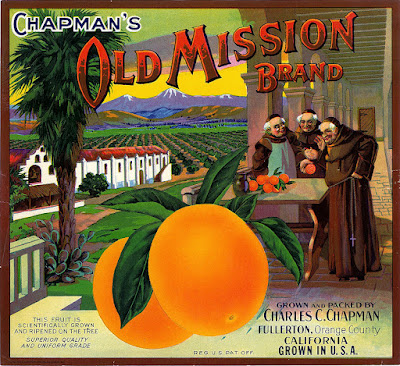

| Old Mission Brand orange crate label from Fullerton, 1920s |

Thus, the name “Orange County” conveyed both obvious and subtle positive connotations to prospective new residents. “The orange,” said California journalist/ethnographer/folklorist Charles Fletcher Lummis, “is not a fruit, but a romance.”

At one point during our nearly twenty-year struggle to separate from Los Angeles, the name "Santa Ana County" was also proposed. But we returned again and again to the moniker “Orange County,” which is what stuck when we finally succeeded (and seceded) in 1889.

J. M. Guinn (1834-1918) of the Historical Society of Southern California wrote that the name “Orange” was selected, “for the sordid purpose of real estate” in the hopes that “Eastern people would be attracted by the name, and would rush to that county to buy orange ranches…”

Santa Ana lawyer Victor Montgomery, who drafted the bill which ultimately allowed for the creation of Orange County, wrote that our new county’s name, would “have more effect in drawing the tide of emigrants to this section than all the pamphlets, agents and other endeavors which have hitherto proved so futile.”

|

| A 1940s Union Pacific Railroad postcard depicts the California dream. |

Indeed, the new county with the sunny, romantic name would draw many thousands (and eventually millions) of new residents from elsewhere. And by happenstance it turned out that our climate and soil actually were perfect for growing citrus – especially the Valencia orange. In fact, the orange would become the mainstay of our whole economy for more than half a century. But the dream – and our romantic name – preceded that very real success.