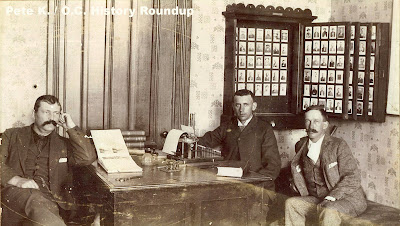

I was recently contacted by Pete K., who just purchased this rare original print of a late-1890s photo of Orange County Sheriff Joseph Nichols and two of his deputies. The image is already known to those who have studied the history of Orange County law enforcement -- but an original print is still an exciting find.

Over the years, I've seen this image captioned with a variety of name IDs, dates, and so forth. Pete's print has this written on the back: “To Filipe Barante. Three of a kind. Joe Nichols, Nov. 23, 1897.” In another spot it is marked “F – de papa – S.A.” These inscriptions by Nichols provide both more clarity and new mysteries.

Although "Felipe Barante and "F - de papa - S.A." don't ring any bells, the fact that Nichols signed it in 1897 puts to bed the long-held notion that the photo was taken in 1898.

Pete wanted to know a little something about the men in the photo. As I dug for information, I was surprised learn the degree to which these three men were connected to so many significant aspects and personalities of our early local history. Undoubtedly, there's much more to be learned about these three, but here's what I turned up so far:

JOSEPH C. NICHOLS

Born in Indiana in August 1860, Joseph Clark “Joe” Nichols arrived in Orange County in the 1880s. While living in Anaheim in 1889, he married Mary Margaret Parker. Together, they would have three daughters: Marguerite Olive (1897-1941), Norma (1894-1989), and Henrietta (1895-1945).

J. C. Nichols served as Orange County’s third Sheriff, from 1895 to 1899 and was the first elected for a newly adopted four-year term. He is remembered for improving inmate record keeping, overseeing the completion of the jail on Courthouse Square (1896), and keeping increasing numbers of transients in check. Although generally well liked and having a well-funded campaign, he was defeated in the election of 1898 by Theo Lacy. His loss was largely due to the national sentiment of the moment, which skewed toward the Democratic Party and their “Free Silver” movement.

After leaving office, Nichols had his own furniture store in Santa Ana. Around 1907 he and his family moved to Los Angeles where he went into the real estate business. He died in Los Angeles on April 27, 1950.

JOHN W. "JACK" LANDELL

Born in Philadelphia in 1866, the oldest of the six children of James and Sally Landell, John W. Landell came to California with his family in the 1870s. He became an insurance salesman and something of a mover-and-shaker in the Anaheim area. He was City Marshal of Anaheim Township for five years circa 1890. (Some newspaper accounts cite him as Anaheim’s Justice of the Peace or Constable, but in he himself described his position as City Marshal in Samuel Armor’s 1921 History of Orange County.) After that, he went to Santa Ana where he worked as a Sheriff’s Deputy for four years. At some point early in his career, he also worked as a Los Angeles Sheriff’s Deputy.

In April 1897 at what’s now Capistrano Beach (then called San-Juan-By-The Sea and later known as Serra), Landell married Soledad Cristina Pryor, daughter of ranchero Pablo Pryor and granddaughter of Don Juan Avila. They would have several children: Gladys (1908–1995), John Paul (1910–1994), and Charles (1901-1933).

Landell resigned his post in Santa Ana in December 1898 and the next month took the position of Justice of the Peace (J. P.) for San Juan Township (San Juan Capistrano area). He held that post for at least 12 years. Afterward, Landell and his wife briefly moved to San Diego, but quickly moved back to Capistrano Beach. He ran again for J.P. of San Juan in 1918 but lost the election. He then focused his attention on his ranch – primarily growing walnuts – and also opened an adjacent auto service station and convenience store. He also served as a member of the local school board.

For most of the rest of his life, he filled in whenever any Orange County J.P. was away due to illness or travel. This included the period from August to December of 1924 when he filled in for Judge Cox of Santa Ana during the illness that would ultimately take Cox’ life. By 1930 Landell was again San Juan’s Justice of the Peace.

He died in San Juan Capistrano on April 4, 1939 and is buried at Anaheim Cemetery.

NATHAN ALLEN ULM

N. A. Ulm was born August 10, 1869 in Jefferson County, Illinois. He arrived in Santa Ana in the late 1880s and married Nellie Jeanette Abercrombie on April 16, 1888. They would have several children: Earl (1890-1925), Nathan Lamar (1892-1957), and Audrey (1894-1960).

Nathan A. Ulm was manager of the Grand Opera House, proprietor of the Santa Ana Book Store, secretary of the Orange County Republican Central Committee, captain in Company L, 7th Regiment (Santa Ana’s National Guard Unit), founding secretary of the Santa Ana Merchants & Manufacturers Association, and generally a prominent figure in the community. Under Sheriff Joe Nichols, he served as the county’s jailer. In 1912, Ulm was part of the posse involved in the infamous 1912 shoot-out in Irvine with the “Tomato Springs Bandit.”

In November 1913 – after a brief investigation --- the State Building & Loan Commissioner George Walker informed the Santa Ana Merchants & Manufacturers Association’s board that their books were short $15,000 to $17,000. Although the Orange County Sheriff’s Department was soon on the case, the Associations’ directors asked that a warrant not be issued Ulm’s immediate arrest but asked instead that he be watched. However, on November 19, Walker went to Ulm and collected the Association’s books from him. Four hours later, Ulm committed suicide by cyanide at his home at 818 E. 2nd Street. Later investigation showed that Ulm had been forging Association president C. D. Ball’s name to help obscure the missing money. The shortfall appeared to date back to 1906.

A few days after his suicide, the Santa Ana Armory Association -- of which Ulm was also secretary -- reviewed their books as well and found $2,500 had somehow gone missing.

In many copies of the 1897 photo of the three lawmen, Ulm is certainly the least remembered today and his name is often misspelled in the caption. But his story certainly turned out to be a colorful one.

If you know more -- and specifically if you know more about "Filipe Barante" or the meaning of "F – de papa – S.A.," drop me a line via email or DM me on Facebook.

%20with%20host%20James%20Smith%20(right).jpg)

%20on%20display%20at%20the%20Old%20Courthouse%20in%202010%20-%20Photo%20by%20Chris%20Jepsen.jpg)

%20and%20friend,%20bear%20hunting,%20circa%201900%20-%20photo%20courtesy%20Orange%20County%20Archives.jpg)